The Ural Owl is a large forest owl found across Europe and northern Asia. It is closely tied to mature woodland and a stable forest environment rather than open land or cities. This species depends on quiet hunting conditions, old trees for nesting, and steady prey populations. Much of its behavior, including breeding success, is influenced by cycles of small mammals, especially voles.

Although the Ural Owl often lives near people, it does not become an urban species. It may tolerate forestry activity or rural settlements, but it continues to rely on natural forest structure. Because of this, the presence of Ural Owls often reflects long term forest health. Learning how this owl flies, hunts, communicates, and chooses habitat helps explain why it thrives in some regions while slowly disappearing from others.

Body Structure and Flight

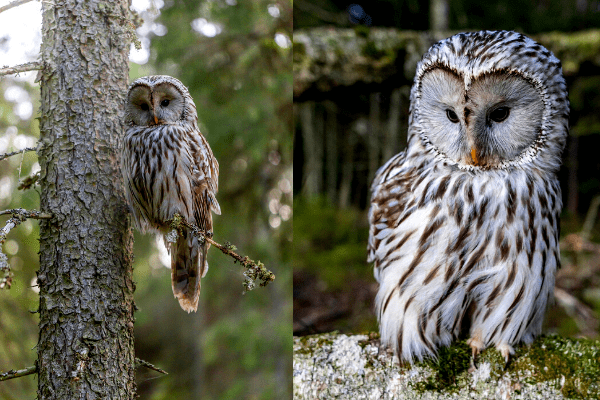

The Ural Owl is not built for speed across open country. Its body reflects a life spent inside forests, where space is tight and movement needs to be deliberate rather than fast. Compared to other large owls, it appears longer and more balanced, with broad wings and an extended tail that help it navigate through trees without sudden loss of control.

This shape allows the owl to fly slowly while remaining stable, an advantage when hunting in woodland where branches, trunks, and uneven terrain leave little room for error.

Flight is also remarkably quiet. Like other forest owls, the Ural Owl has specialized feather edges that soften the sound of air moving over the wings. In low light conditions, prey animals depend heavily on hearing to detect danger. The owl’s near silent approach gives it a clear advantage, especially when hunting small mammals hidden under leaf litter or light snow.

The long tail adds further control, acting as a stabilizer during short glides, sharp turns, and careful landings near nest cavities or favored perches. Every part of the Ural Owl’s flight reflects precision rather than power, shaped by the demands of life in dense woodland.

Vocal Signals and Hearing

Sound plays a central role in the life of a Ural Owl. In dense forest, where visibility is limited even in daylight, vocal communication becomes the most reliable way to maintain contact, defend space, and coordinate breeding. The calls of the Ural Owl are low in pitch and carry well through woodland, traveling farther than higher sounds that are easily absorbed by vegetation. These calls are most often heard at night or during the breeding season, when territories are actively maintained.

Hearing is equally important for hunting. The Ural Owl is capable of locating prey it cannot see, including small mammals moving beneath leaves or snow. Its facial disc is shaped to direct sound toward the ears, and the ears themselves are positioned unevenly on the skull. This asymmetry allows the owl to judge the direction and distance of sounds with high precision. In forest environments, where prey is often concealed, this ability can matter more than vision. Together, vocal communication and acute hearing allow the Ural Owl to function effectively in habitats where sound, rather than sight, provides the clearest information.

Species Classification

The Ural Owl belongs to the genus Strix, a group of owls that are closely associated with forest habitats and low light hunting. This placement is well supported and has remained stable for many years. Researchers have reached this conclusion by comparing body structure, vocal patterns, and genetic data, all of which place the Ural Owl firmly within this group of woodland specialists.

Across its broad range, several subspecies have been described, largely based on regional differences in size and plumage. These variations are gradual and blend into one another rather than forming clear boundaries. For this reason, all populations are treated as a single species. The differences seen from one region to another reflect local environmental conditions rather than long periods of separate evolution.

Similar Species and Field Confusion

In the field, the Ural Owl is most often confused with other large forest owls that share parts of its range. The Tawny Owl and the Great Grey Owl are the two species that cause the most confusion, particularly in low light or when views are brief. At a distance, overall size alone can be misleading, especially when juveniles are involved.

Closer observation usually resolves the uncertainty. The Ural Owl has a longer, more elongated appearance when perched, with a tail that extends noticeably beyond the folded wings. Its posture is upright, giving it a stretched look compared to the more compact Tawny Owl.

When compared to the Great Grey Owl, the Ural Owl appears less bulky, with a smaller facial disc and a more streamlined head shape. These differences are subtle but consistent, and experienced observers rely on them to separate the species reliably in forest conditions.

Geographic Variation

The Ural Owl occupies an unusually large range, stretching from central Europe across Scandinavia and deep into northern Asia. Over this distance, the species shows noticeable but subtle variation. Owls from northern regions tend to be larger and paler, while those from more southern forests are often slightly smaller with darker plumage. These differences are not sharp or easily separated, but instead shift gradually across the landscape.

Southern Populations

Often slightly smaller with darker plumage, reflecting forest type and local environmental conditions.

Northern Populations

Tend to be larger and paler, a pattern commonly seen in forest birds living at higher latitudes.

Such variation is closely tied to local conditions. Climate influences body size, prey availability shapes hunting behavior, and forest type affects coloration. Vocal differences have also been noted, but these are minor and do not form clear regional patterns. Because these traits change slowly from one area to the next, researchers treat the Ural Owl as a single widespread species rather than a collection of distinct forms. This continuity reflects adaptation to environment rather than long-term isolation.

Range and Forest Dependence

On a map, the Ural Owl appears widespread, stretching from central Europe through Scandinavia and far into northern Asia. On the ground, its presence feels much more selective. You do not find this owl just anywhere within that range. It stays close to forest, and usually to forests that have been standing for a long time.

The Ural Owl depends on continuous woodland rather than isolated patches of trees. Large forests allow it to hunt without interruption, establish stable territories, and return to the same nesting areas year after year. When forests are broken up by roads, clearings, or heavy logging, the species becomes less reliable, even if food and climate seem suitable. This close link to forest structure explains why the Ural Owl can persist quietly in some regions while fading from others where the forest itself is slowly changing.

Habitat Use and Nest Sites

Ural Owls are most at home in mature forests where old trees are still part of the landscape. These forests offer more than just cover. Large, aging trees provide natural cavities that the owls rely on for nesting, while a relatively open forest floor allows easier movement and hunting. Dense undergrowth or heavily altered forest structure tends to make an area less suitable, even if prey is present.

Nest site availability plays a decisive role in breeding success. In many managed forests, old cavity bearing trees have become rare, and with them, suitable nesting places. Where researchers and conservationists have installed nest boxes, breeding rates have often increased noticeably. This has shown that, in many areas, food alone is not the limiting factor. Without safe and stable nesting sites, even healthy forests may fail to support breeding pairs over the long term.

Activity Patterns

Ural Owls are most active at night, when forests are quieter and hunting conditions are best. During the breeding season, however, their daily rhythm becomes more flexible. Adults may be seen moving at dusk, dawn, or even in full daylight as they make repeated trips to feed their chicks. This daytime activity is most noticeable in years when prey is abundant and hunting is efficient.

Once the breeding season ends, activity levels drop sharply. The owls spend much of their time roosting, often in the same sheltered spots day after day. By limiting unnecessary movement, they conserve energy during periods when food is less predictable. This pattern reflects a careful balance between effort and reward, shaped by prey availability rather than fixed clock based behavior.

Territorial Behavior

Ural Owls are known for their strong territorial defense, especially during the nesting period. When eggs or chicks are present, adults react quickly to anything that comes too close to the nest. This can include large mammals and, in some regions, people who unknowingly approach a nesting area. Such responses are not signs of aggression by nature, but of strong parental investment.

Breeding opportunities for Ural Owls are closely tied to prey cycles, and a failed nest may mean waiting another year before conditions improve. Because of this, adults defend their territory intensely during successful breeding seasons. Territory size and behavior also shift with prey availability. When food is abundant, territories may be smaller and more stable. In poorer years, owls range more widely, adjusting their space use to changing conditions.

Diet and Prey Cycles

Small mammals form the foundation of the Ural Owl’s diet, with voles playing the most important role. In years when vole populations are high, Ural Owls often breed successfully, raising larger broods with less effort. When vole numbers decline, breeding may be delayed or skipped altogether. These cycles have been observed repeatedly across the species’ range and are one of the strongest factors shaping its population trends.

Although Ural Owls are capable of taking birds, amphibians, and occasionally larger prey, these food sources are secondary. They help the owl survive lean periods but do not fully replace the energy provided by small mammals. This strong reliance on vole populations makes the species sensitive to changes in prey dynamics caused by habitat alteration or climate driven shifts. In many regions, the health of Ural Owl populations closely mirrors the rise and fall of the animals they hunt.

Conservation Status and Trends

At a global level, the Ural Owl is classified as Least Concern, reflecting its wide range and healthy numbers in some parts of Europe and northern Asia. This label, however, can be misleading. When populations are examined region by region, a more uneven picture emerges. In areas where forests are heavily logged or broken into smaller fragments, numbers have declined, sometimes quietly and without immediate notice.

Conservation Status and Trends

IUCN: Least ConcernStable or Increasing

Regions with continuous forest cover, protected old trees, and available nesting sites continue to support stable breeding populations.

Local Declines

Intensively managed forests and fragmented landscapes often show gradual loss of breeding pairs over time.

Long term studies show that Ural Owl populations remain stable or even increase where forest management allows old trees to persist and nesting sites are protected. In contrast, landscapes that prioritize timber extraction over forest structure tend to lose breeding pairs over time. These trends highlight an important point. The future of the Ural Owl depends less on short term protection and more on how forests are managed across decades.

Source Link – Click here

Living Near People Without Becoming Urban

Ural Owls often live closer to people than many expect, but always on their own terms. They may nest near farms, forest tracks, or small villages, especially in landscapes where traditional forestry has left large trees standing. In these places, human activity is predictable and relatively quiet, and the forest still functions as a forest. As long as disturbance remains low, the owls often ignore nearby human presence entirely.

Cities are a different matter. Urban environments replace darkness with artificial light, silence with constant noise, and old trees with buildings. Suitable nest sites disappear, hunting becomes unreliable, and the sound based hunting strategy that works so well in forests begins to fail. Because of this, Ural Owls do not make the transition into true urban life. They remain tied to natural structure, even when that structure exists close to people. This balance explains why the species can appear tolerant of humans while still remaining firmly wild, shaped far more by forest conditions than by proximity to civilization.

Related Post

- Rufous Owl : A to Z Guide

- What Does A White Owl Mean : A to Z Explanation

- Do Owls Eat Birds : Let’s Understand Why

- Baby Great Horned Owl – A to Z Guide