Owls do have tongues, but they are extremely different from mammal tongues and even most bird tongues. Scientific studies on raptor oral anatomy show that an owl’s tongue is small, thin, and deeply set inside the beak, supported by a rigid hyoid apparatus that restricts its ability to move or extend outward. Instead of helping in tasting or manipulating food, the owl tongue plays a narrow mechanical role: pushing swallowed prey toward the throat.

Owls depend on their sensory adaptations, talons, and beak to hunt, while their tongue remains a minimal, internal tool. Baby owls use their tongues the same way adults do, and research confirms that owls have very few taste buds, making flavor detection almost irrelevant in their feeding behavior.

A Clear Look at an Owl’s Tongue and Its Hidden Structure

Although owls have tongues, they look nothing like what people imagine. Scientific dissections and avian anatomy research show the tongue is small, pointed, and located deep inside the beak, supported by a shortened hyoid bone system that limits mobility. This anatomical configuration is consistent across owl species from Barn Owls to Great Horned Owls and explains why their tongue is rarely seen.

The surface is covered in backward-facing papillae, small keratinized projections that help direct prey into the esophagus. Because owls swallow prey whole or in large chunks, their tongue never evolved for tasting, chewing, grooming, or licking-only for guiding food inward.

Key Verified Features:

- Short, narrow, pointed tongue

- Supported by a rigid hyoid apparatus

- Covered in papillae for moving prey backward

- Sits deep inside the beak and rarely visible

- Not built for licking or object manipulation

How an Owl’s Tongue Helps Its Deadly Hunting Precision

Owls are deadly hunters because of their silent flight, binocular vision, and highly sensitive hearing not because of their tongue. Their tongue has no role in detecting prey or processing it before swallowing. Instead, the tongue becomes relevant only after the prey is caught and the beak begins tearing it or swallowing it whole.

Its job is to align pieces of fur, feathers, bones, and tissue so they can move smoothly into the esophagus, which is essential for pellet formation later. This means the owl tongue contributes to feeding efficiency, not hunting accuracy.

Verified Tongue Functions:

- Helps align prey before swallowing

- Supports movement toward the throat

- Works with throat muscles, not beak muscles

- Prevents prey from slipping forward

- Aids in consistent pellet formation

Do Baby Owls Use Their Tongue Differently Than Adults?

Baby owls (owlets) show nearly identical tongue function to adults despite their smaller size. Nest studies and rehabilitation records confirm that parents provide pre-torn prey pieces to owlets, meaning babies don’t need to manipulate or chew food.

Their swallowing reflex is strong and instinctive, and the tongue supports this process by guiding food inward. As they mature and begin swallowing larger chunks, the tongue maintains the same functional role. There is no stage of growth where owlets use their tongue more actively or differently.

What Research Shows About Owlets:

- Identical tongue structure to adults

- Parents tear prey, so no need for tongue manipulation

- Tongue helps with positioning food for swallowing

- No chewing or repositioning behavior

- Function remains constant as they age

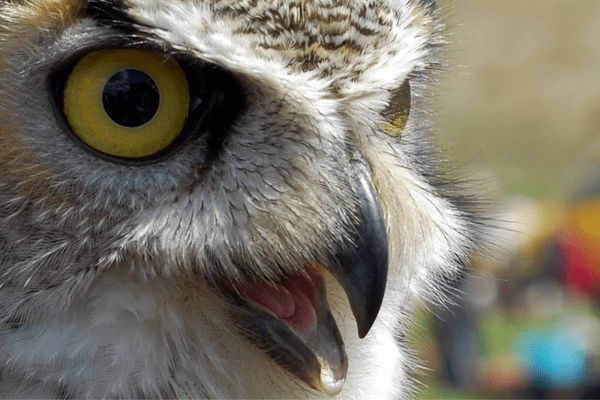

Could an Owl Lick? The Truth Behind Their Limited Tongue Movement

Owls cannot lick biology makes it impossible. The hyoid apparatus that supports the tongue is unusually short and rigid in owls, unlike the elongated and flexible version seen in species like woodpeckers or hummingbirds. This prevents the tongue from extending outward or performing complex motions. Owl behavior supports this anatomy: they never lick objects, clean themselves with their tongue, or use it to interact with prey. All observed tongue movements occur inside the Owl Beak and are tied to swallowing or panting.

Why Licking Is Not Possible:

- Hyoid bones restrict outward extension

- Tongue musculature is limited

- No evolutionary need for licking

- Tongue stays entirely inside the beak

- All movement linked to swallowing reflexes

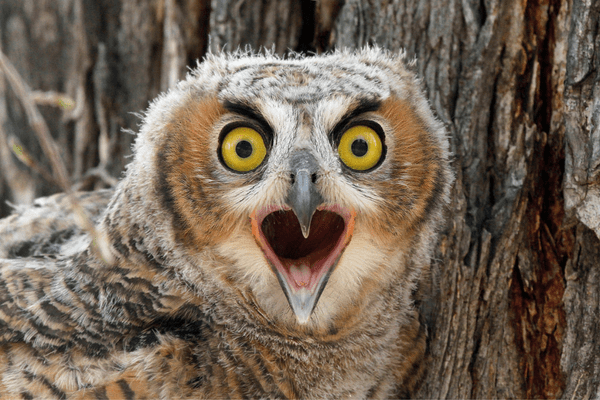

What Happens When an Owl Tries to Move Its Tongue

When an owl moves its tongue, the movement is subtle and almost entirely internal. Veterinary examinations show that the tongue shifts slightly backward or upward when the owl swallows, pants, or yawns. It never appears outside the beak, nor does it move prey around. This limited range is due to the tongue’s internal anchoring and the species’ strict adaptation to swallowing whole prey.

Observed Real Movements:

- Moves backward, not forward

- Visible only during panting or yawning

- Minimal muscular control

- Used to push prey toward the pharynx

- Not used for licking or probing

The Role of Taste Buds: Do Owl Tongues Sense Flavor?

Owls can sense taste, but only in a limited way. Scientific studies on avian gustation report that owls have around 50–60 taste buds, which is extremely low compared to mammals and even many birds. These taste receptors are clustered near the back of the tongue and upper throat, where they play a minor role in identifying basic sensory signals. Because owls are strict carnivores that swallow prey quickly, complex taste detection isn’t necessary. Their hunting and feeding choices rely on vision and hearing rather than flavor.

Taste System Facts:

- Very few taste buds

- Taste not involved in prey selection

- Taste buds located near throat, not tongue tip

- Matches patterns in other carnivorous raptors

- Tongue adapted more for swallowing than tasting

Related Post

- Leucistic Owls: Understanding a Rare Genetic Phenomenon

- Do Barred Owls Eat Squirrels : Uncovering the Truth

- Barn Owl Skull: A Look into Nature’s Design

- Barn Owl Feet: Understanding the Unique Anatomy

- Tawny Fish Owl: Facts, Habitat, and Conservation Efforts

- Rufous Owl : A to Z Guide

- What Does A White Owl Mean : A to Z Explanation

- Do Owls Eat Birds : Let’s Understand Why

- Baby Great Horned Owl – A to Z Guide

- Flammulated Owl : A to Z Guide