The Philippine Eagle-Owl (Bubo philippensis) is one of the largest owls found in the Philippines, yet it remains surprisingly easy to overlook. It lives only within the country’s islands, mostly in forested areas where human activity thins out and night sounds take over. Despite the name, it has no connection to the Philippine Eagle. “Eagle-owl” is simply a reference to its size and heavy, powerful build.

This owl hunts at night, usually from a perch, listening more than moving. Instead of chasing prey, it waits. When it calls, the sound carries far through the forest. These calls are not casual noises but serve a purpose-marking territory and keeping distance from other owls in places where sight is limited.

Because the Philippines is made up of many islands, populations of this owl show small differences in appearance and behavior. Much of this variation is still poorly studied, not because the owl is extremely rare, but because it is quiet, nocturnal, and difficult to observe.

Today, forest loss remains the main threat. As lowland forests shrink, the Philippine Eagle-Owl is pushed into fewer suitable areas, making conservation efforts increasingly important.

Species Classification and Scientific History

The Philippine Eagle-Owl goes by the scientific name Bubo philippensis and sits within the owl family Strigidae, alongside most of the owls people are familiar with. It belongs to the genus Bubo, a group made up of large, heavy-bodied owls that tend to leave a strong impression.

The term “eagle-owl” often causes confusion. It does not mean the species is related to eagles. Early naturalists used the label simply because of its size, strength, and the way it dominates a forest setting once night falls.

Species Classification

The species entered scientific records in 1851, when German naturalist Johann Jakob Kaup formally described it. Based on the limited specimens available at the time, Kaup believed the owl was unusual enough to deserve its own genus.

He named it Pseudoptynx and gave it the species name philippensis. This was not an unusual decision in the nineteenth century. Birds from the Philippines were poorly represented in European collections, and direct field observations were rare.

As more owl species were studied and compared, those early conclusions began to shift. Similarities with other large Asian owls became clearer, and the Philippine Eagle-Owl was eventually placed within Bubo, where most authorities list it today.

Recognized Subspecies

Some taxonomic lists still associate it with the closely related genus Ketupa, reflecting ongoing debate rather than confusion. Its classification history is a good example of how science works in practice. Names change not because earlier scientists were careless, but because better information slowly replaces incomplete evidence.

Physical Features and Overall Appearance

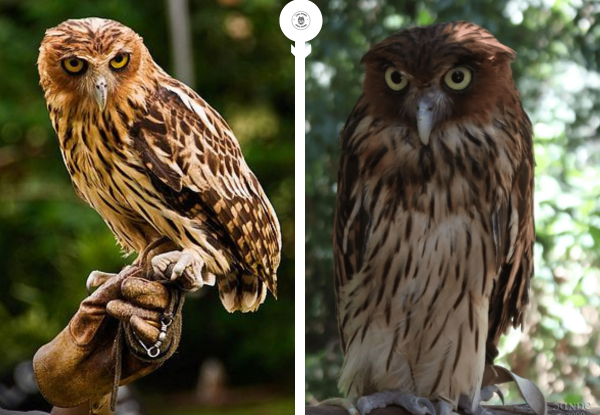

The Philippine Eagle-Owl is a large, heavy-bodied owl that looks built for control rather than speed. It has a broad head, noticeable ear tufts, and thick, powerful legs that give it a solid, almost grounded appearance.

In the forest, it does not look sleek or delicate. It looks capable. This impression is reinforced by its talons, which are strong and well suited for holding struggling prey once it is caught.

Physical Features

Its plumage is mostly brown, broken up by darker streaks and mottling. This pattern is not decorative. It closely matches the texture of tree bark and shadowed foliage, allowing the owl to remain surprisingly hard to spot during the day when it is roosting. The facial disk is present but not as sharply defined as in smaller owl species. Even so, it still plays an important role in directing sound toward the ears, an advantage when hunting in low light.

At night, size becomes its most striking feature. The wings are broad rather than narrow, designed for steady, controlled flight through forest gaps instead of rapid chases. When light briefly catches its face, the orange to yellow eyes tend to stand out first, often the only clear sign that a large owl is watching from nearby.

Variation Across Philippine Island Populations

The Philippines is not a single continuous landmass, and that matters when it comes to how animals evolve. The Philippine Eagle-Owl has spent thousands of years living on separate islands, often with limited movement between them. Over time, that isolation has quietly shaped small differences between populations, even though they are still considered the same species.

Some owls appear slightly larger or darker depending on the island they come from, while others show minor changes in feather patterning. These differences are easy to miss unless birds are compared closely, which is one reason they are not widely documented.

They are not dramatic enough to suggest separate species, but they do point toward local adaptation. Forest structure, prey availability, and even climate can influence how these owls develop from one island to another.

Vocal differences may also exist, particularly in call pitch or rhythm, but this area remains poorly studied. Because the species is nocturnal and difficult to observe, many islands have never been surveyed in detail.

As a result, scientists suspect that additional variation is present but simply has not been recorded yet. What we see now is likely only part of the full picture, shaped as much by limited research as by biology itself.

Natural Habitat and Range Within the Philippines

The Philippine Eagle-Owl is most closely tied to forested landscapes, particularly lowland and mid-elevation forests where large trees are still present. These areas provide what the owl needs to get through the day and the night.

During daylight hours, it roosts quietly in tall trees where dense foliage and shade offer protection. After dark, it relies on a more open forest floor and understory to hunt effectively.

While the species can survive in forests that have been selectively logged, it does not adapt well to heavily altered environments. It is rarely found far from forest cover and generally avoids areas where trees have been cleared completely.

As forests thin out, suitable roosting sites become harder to find, and hunting becomes less efficient. The owl’s range covers several major islands across the Philippines, but its presence is not evenly spread.

In many regions, remaining habitat exists only as scattered patches. This fragmentation forces individuals into smaller areas, limiting territory size and reducing access to prey.

Over time, these constraints can affect breeding success and survival, even in places where the owl is still present. The species’ distribution today reflects not just where forests exist, but how intact and connected those forests remain.

Vocal Behavior and Territorial Signaling

Sound plays a major role in how the Philippine Eagle-Owl navigates its world. In dense forest, where visibility drops quickly after sunset, vocal communication becomes far more reliable than sight. The owl’s calls are deep and low in pitch, designed to travel long distances through thick vegetation without losing clarity. These calls are not random night noises. They serve a clear purpose and are used deliberately.

Vocal Behavior

Territorial signaling is one of their main functions. By calling from favored perches, an owl announces that an area is already occupied, reducing the need for physical confrontation with others of its kind.

This is especially important in forests where encounters could otherwise be sudden and costly. During the breeding season, calling becomes more frequent and more intense, as defending territory directly affects nesting success and access to food.

For researchers, these vocalizations are often the only reliable sign that the species is present. The Philippine Eagle-Owl is difficult to observe visually, even where it still exists in good numbers.

As a result, population surveys frequently rely on call detection rather than sightings. In many cases, the owl is heard long before it is ever seen, if it is seen at all.

Records of Captive Care and Breeding Attempts

For many years, the Philippine Eagle-Owl was considered almost impossible to breed in captivity. That assumption changed in the mid-2000s, when a conservation center in the Philippines quietly made history.

In 2005, the Negros Forests and Ecological Foundation (NFEFI) in Bacolod documented the first successful captive hatching of a Philippine Eagle-Owl, a milestone that attracted international attention among owl specialists.

The achievement did not happen overnight. Several years earlier, NFEFI had arranged the transfer of captive eagle-owls from a DENR-accredited zoological facility, allowing the birds time to settle and form natural pair bonds. Only one pair showed clear courtship behavior, and even then, breeding success was far from guaranteed.

When an owlet was finally discovered in the nest, already a few days old, it confirmed that the species could reproduce under carefully managed conditions. The chick was raised by its parents, with minimal interference, offering rare insight into captive rearing behavior.

A second successful hatching followed the next year, supported by international conservation partners. Despite these successes, captive breeding remains extremely rare.

The Philippine Eagle-Owl does not adjust easily to artificial settings, and even well-designed facilities face challenges related to stress and disturbance. For this reason, conservation efforts continue to prioritize habitat protection over large-scale captive programs.

While hunting of the species is illegal in the Philippines, enforcement remains uneven in some areas. This reality reinforces an important lesson from the captive breeding story: safeguarding forests and reducing human pressure remain far more effective for the owl’s survival than relying on captivity alone. ( Source Link – Click )

Early Growth and Development of Young Owls

Like most large owls, Philippine Eagle-Owl chicks hatch in a very undeveloped state. At first, they are completely dependent on the adults for warmth, protection, and food. They cannot regulate their own body temperature and are unable to feed themselves.

During these early days, the nest is the center of survival. If food is scarce or the nesting site is disturbed, chicks have little chance of making it through this stage.

Growth during the first weeks is surprisingly fast. Parents bring prey to the nest and tear it into small, manageable pieces before offering it to the chicks. As the young owls grow stronger, the size of the food gradually increases, allowing them to develop the strength and coordination needed for feeding on their own.

Throughout this period, adult care remains constant, and successful rearing depends heavily on steady prey availability and a secure nesting location.

After fledging, young owls do not immediately become independent. They stay close to the nesting area for several weeks, continuing to rely on adults while learning how to hunt and navigate the forest at night.

This stage is one of the most dangerous parts of their life. In fragmented forests, juveniles face higher risks from predators, human activity, and habitat gaps. Many do not survive this transition, making early development a critical bottleneck for the species’ long-term survival.

Conservation Status and Ongoing Threats

The Philippine Eagle-Owl is currently classified as Vulnerable, a status that reflects a continuing decline rather than a sudden collapse. The main reason is straightforward and familiar across much of the Philippines: the steady loss of lowland forest. These forests are cleared or broken apart by logging, agricultural expansion, and infrastructure projects, leaving the owl with fewer places to roost, hunt, and breed.

Conservation Status

Habitat loss does not affect the species all at once. Instead, it slowly compresses populations into smaller and more isolated forest patches. As territories shrink, prey becomes harder to find and breeding opportunities decline.

Even though the Philippine Eagle-Owl can tolerate some level of disturbance and has been recorded in selectively logged forests, there is a clear limit to that flexibility. Once large trees disappear and forest cover becomes fragmented, the environment no longer supports its basic needs.

Hunting and capture add further pressure, even though the species is legally protected in the Philippines. Enforcement is uneven, particularly in rural areas where traditional hunting practices and limited awareness still exist. These threats, combined with habitat fragmentation, make long-term survival increasingly uncertain.

Protecting remaining forest and maintaining large, connected habitat areas remain the most effective conservation measures. Without them, even resilient species like the Philippine Eagle-Owl gradually fade from landscapes they once occupied with ease.